The January 2025 fires in Los Angeles made clear an issue that has been brewing for years: as wildfires become more urban in nature, what is the role of urban water systems in their prevention, response and recovery?

In the last decade, wildfires in Colorado and Northern California revealed how fire can disrupt water supply and distribution systems and have long-term impacts for recovery.

In response, we at UCLA and UC Agriculture and Natural Resources (UC ANR) held an in-person workshop in 2021 and authored a report, Wildfire and Water Supply in California, addressing early questions of water system preparedness for increasingly catastrophic wildfires in urban areas.

Following the disastrous 2025 fires in Los Angeles—and increasing national attention to issues of water supply and availability for urban fires—we developed a set of frequently asked questions to directly respond to related challenges

Yet, big questions remain: How should water systems prepare for 21st century wildfire events? What policy changes and infrastructure investments are needed to increase resilience?

To address these questions, researchers at UCLA's Luskin Center for Innovation, UC ANR's California Institute for Water Resources, and Arizona State University are partnering again to host a series of four workshops through a water supply + wildfire research and policy coordination network.

The work, which aims to strengthen preparedness and recovery at the water-fire nexus, is primarily funded by UCLA’s Sustainable LA Grand Challenge.

Water systems and wildfire fighting capacity

The first event in the series was held in August 2025. Forty-two participants gathered at the UC Sacramento Center for a workshop focused on the capacities and limitations of water supply systems to fight wildfire in wildfire-prone areas—motivated by policymaker and public reactions in the wake of the LA fires.

Misinformation and a fractured media environment have fueled the discussion around expectations for water systems during wildfire events. The water sector can improve communication to enhance public understanding on how urban water systems function to help establish what is reasonable and affordable for water systems investments.

At the same time, some water systems are looking to increase preparedness and infrastructure for wildfire fighting.

A temporary window of political will exists to explore feasible investments in this capacity.

Participants represented water systems, water industry associations, non-profit organizations, regulators, technical assistance providers, fire protection experts, engineering consultants and researchers from across California and beyond. The workshop included panels with experts and collaborative activities.

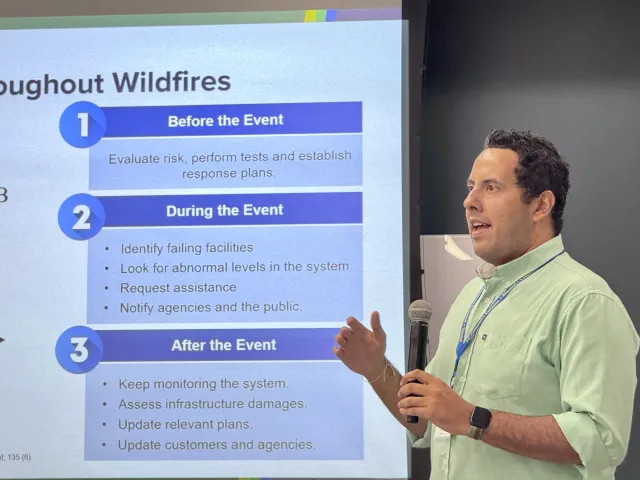

Erik Porse and Greg Pierce began the event by framing the day’s focus. In the morning, Camilo Salcedo led a panel discussion of experts on how to think better, but realistically, about water distribution systems. Pierce then kicked off a focused discussion, informed by four expert lightning talks, on potential options for state-level best practices and standards to assess water systems’ wildfire fighting capacities.

In the afternoon, Edith de Guzman and Faith Kearns led a guided exercise for small, rotating participant groups, using a worksheet focused on specific water system priorities and constraints for enhancing their wildfire fighting capacity. Kearns then led an open reflection on themes of the day, and Porse closed the day with reflections.

Camilo Salcedo leading panel discussions.

Preliminary takeaways

The presenters and participants provided a diverse range of experiences and expert insights on the possibilities and limitations of increased wildfire fighting capacity for water systems, including five major themes.

1. Wildfire fighting is NOT a primary responsibility or capability for water systems

As is widely understood in the water and disaster response industries, participants at the workshop echoed the idea that no water system can reasonably expect to “stop” large urban wildfires.

Fire hydrants are not designed to meet demand of fighting large-scale wildfires involving entire blocks or neighborhoods. During a large urban wildfire event, fire hydrants will “run out of water” given the shifting scope of urban wildfires, the scale and speeds of which have been increasing.

Moreover, water supply is only one element of wildfire-fighting, and, with limited resources, we should invest in other areas first from a cost-benefit perspective.

However, these kinds of broader considerations and cost-benefit analyses between water supply enhancements for firefighting, much less across broader wildfire mitigation techniques, have not been rigorously conducted and thus it is hard to narrow down final recommendations without further study.

2. Enhanced firefighting capacity in water systems is expensive and conflicts with core mandates

There are profound funding and willingness-to-pay limitations for water infrastructure generally, and few if any funding sources. We will explore these topics further in Workshop 2.

Moreover, while there may be potential synergies for investments by water supply agencies in wildfire prevention that can also increase system resilience for other needs, there are difficult tradeoffs beyond their monetary cost. For instance, drinking water quality and core Safe Drinking Water Act regulatory compliance can be compromised.

Other tradeoffs need to be considered related to existing regulations, safety and public health, such as for vector control or earthquake resilience. And also for broader issues, including NIMBY resistance related to aesthetics and public space use to new above-ground infrastructure.

3. “Soft” management and coordination interventions are just as important as “hard” infrastructure upgrades

Even when we look to potential ways to enhance water systems’ wildfire fighting capacities, workshop participants stressed “soft” interventions were just as, if not more, important and feasible as “hard” infrastructure upgrades (pipes, hydrants, pumps, etc.) which the general public and policymakers tend to think of first.

The soft interventions stressed as most important were enhanced and specified coordination before wildfires in areas of risk and more formal agreements between fire agencies and emergency operation centers (EOCs), which can all be mobilized better during fire events.

A key sub-theme of this emphasis was that water systems are eager to enhance these relationships and agreements, but need more recognition and buy-in from fire agencies and EOCs.

4. There are mixed opinions on whether or how to provide statewide best practices or standards

There are currently no standard requirements or formalized best practices for water supply systems to fight wildfires, so workshop participants explored what, if any, role statewide guidance, standards and frameworks related to water supply and wildfire fighting should play.

There is a potential opportunity to at least provide best practices for cross-learning between systems, but also many downsides especially to rigid standards that are unfunded mandates and legal liabilities.

A long implementation timeline would be required depending on the framework, differentiated by system size and risk. There was no simple consensus on this topic at the workshop, but we committed to exploring more in a peer-reviewed paper we are writing.

5. There are interesting examples to follow and ideas to try, but firm recommendations will take time

In addition, participants noted numerous other strategies used by systems across California to increase available water supply during wildfires.

These included hard infrastructure interventions such as the City of Berkeley’s modular sea water pumping system as well as advanced water-fire agency collaboration efforts in Lake County. It remains an open question, however, whether these promising examples can scale or be replicated.

Participants providing to summary contributions for potential adaptation options and policy recommendations (Esther Lofton, UC ANR Cooperative Extension Advisor)

Next Steps

The discussion of whether, where and which wildfire fighting interventions make most sense to pursue further for water systems largely remains in its infancy. It is just as important to identify which of the above parameters should not be considered for further evaluation or investment as to identify those that should.

We will be releasing a publicly-available synthesis report in the fall of 2025 to dive deeper into many of these issues.

Even as scientific research is still understanding how wildfires can damage a water system and the ways that contamination spreads in a system, cities in California and throughout the west are facing decisions now.

Collecting expertise from the water industry, firefighters, water supply and quality researchers, policymakers and affected communities can help address the challenging questions faced in adapting to 21st century wildfires.

---

Greg Pierce is the Senior Director of the Luskin Center for Innovation, an Associate Professor in Residence at UCLA's Department of Urban Planning, and the director of the Human Right to Water Solutions Lab.

Erik Porse is the Director of the California Institute for Water Resources and an Associate Cooperative Extension Specialist in UC ANR.

Faith Kearns is a scientist and research communication practitioner, the Director of Research Communication with the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative, and an Affiliate Scholar with the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

Edith de Guzman is a Water Equity and Adaptation Policy Cooperative Extension Specialist based in UCLA's Luskin Center for Innovation.

Camilo Salcedo is a Project Scientist with UC ANR's California Institute for Water Resources.

Jason Islas is the Assistant Director for Marketing and Communications at UCLA's Sustainable LA Grand Challenge.

Ariana Hernandez is a Project Manager in UCLA's Luskin Center for Innovation.