Two worms and one idea (monitoring): One of the main challenges to growing tree fruits are pests that can destroy the fruit or make it unmarketable. Some pests can injure the trees directly, affecting their growth.

The oriental fruit moth (scientific name, Grapholita molesta) and the peach twig borer (Anarsia lineatella) are two important pests of peaches, nectarines, and other stone fruits that can do both. Insecticide applications are often used to control these pests, though mating disruption is an alternative that may be effective alone or as a complement to chemical control. For pesticide applications to be effective, timing is of the essence, and monitoring pest activity and pressure is one of the cornerstones of integrated pest management, and of sustainable pest management practices, in general. Over the last two years, we monitored the adults of these caterpillar pests at two sites in eastern Contra Costa county using pheromone traps. The results highlight the importance of monitoring pest populations for appropriate and well-timed control measures. Read on to learn about these pests and what monitoring in our region has revealed, so far. If you are a producer of stone fruit in the Mt. Diablo region, I hope to hear from you as I work to expand this work and explore opportunities for making management of these pests more effective and less costly.

Meet the pests: Before we get into what we have seen over the past two seasons, let's take a closer look at the biology and behavior of these pests. As pests of stone fruit, these two insects have many similarities and some important differences. Despite their names suggesting distinct targets, both species attack the young, tender shoots and developing fruit of peaches, nectarines, and various other fruit trees. Their life cycles are similar in that both emerge as caterpillars in the spring that first feed on tender, new shoot tips, causing them to dieback (called "strikes"), while subsequent generations preferentially shift to maturing fruit. For this reason, the

later generations are of main concern for potentially damaging the harvest. That said, high populations may cause significant injury to new growth early in the season, and can especially damage trees in young orchards with a lot of young growth and where trees are still establishing their shape.

The adults of both the oriental fruit moth (OFM, for short, and not to be confused with oriental fruit fly) and the peach twig borer (PTB, for short) are rather nondescript small, gray-brown moths (one distinguishing feature of PTB are a set of appendages that protrude from the head of the moth that give it a "snout-like" appearance). The worm-like caterpillar larval life stage of each pest, which damage shoots and fruit by feeding in them, are more distinct in both appearance and behavior. Larvae of OFM are uniformly cream-colored over the length of their body while the full-size larvae of PTB are characterized by distinct dark and light bands. Larvae of both of these insects often enter the fruit around the stem. OFM larvae bore down toward the center of the fruit and feed around the pit, while PTB larvae penetrate the fruit and tend to feed just under the surface. Both species bore into young, tender growing shoots early in the spring when no fruit is available and feed inside the stems, destroying them from the inside and causing them to wilt and dieback. As fruit begin to turn color and mature during the season, both pest species prefer to lay eggs on fruit which are then penetrated by the hatching worms.

Both pest species survive the winter when trees are dormant in an inactive, immature form in "nooks and crannies" (protected cavities) on the tree

bark or in debris on the ground. They emerge around the time of bloom and find vegetative growth or flowers to bore into, where they feed, causing damage. When mature, this first generation pupate and eventually give rise to the first adult moths of the season. Pheromone baited sticky traps can be used to capture this "first flight" and to thereby identify when the pests have become active. Given that the development of insects is highly dependent on temperature, scientists have developed models that can predict the rate of development of each generation of pest based on its specific characteristics. These "degree day" models can help predict how a population may hit a critical threshold of economically significant damage to fruit crops (stay tuned for another post on growing degree day models in the near future). As it takes time for populations to build up to damaging levels, insecticide sprays are not usually recommended until the "second flight" is expected based on degree day accumulation. A combination of monitoring accumulating degree days (by applying current season temperature records to the model) and monitoring pest activity with pheromone traps can help track the level of pest pressure and determine optimal times to apply control measures. These monitoring methods should be combined with observations in the orchard for strikes as well as sampling ahead of harvest to assess fruit damage and the overall effectiveness of the current control practices.

Control strategies: In general, recommendations for controlling these pests are well-timed insecticide applications, including some materials approved for organic farming methods (see UC IPM links below). Broad spectrum insecticides can unfortunately diminish the presence of "natural enemies" in the orchard, so it is best to keep applications to the minimum necessary. Natural enemies are typically insects or other invertebrates that prey on pest species and that can thereby reduce damage from these pests. Mating disruption, an alternative management practice which entails the saturation of orchard air with the pest's sex pheromone, disrupting the ability of males to home in on females, is suggested as a viable option for OFM, and a complementary practice to increase the efficacy of an insecticide program for PTB. Knowing to what degree each pest is of concern can help with choosing suitable control measures, and making applications more effective. Consult your PCA regarding specific materials and remember that the pesticide "label is the law." Not only that, it is also the first source of information for using the material safely and effectively.

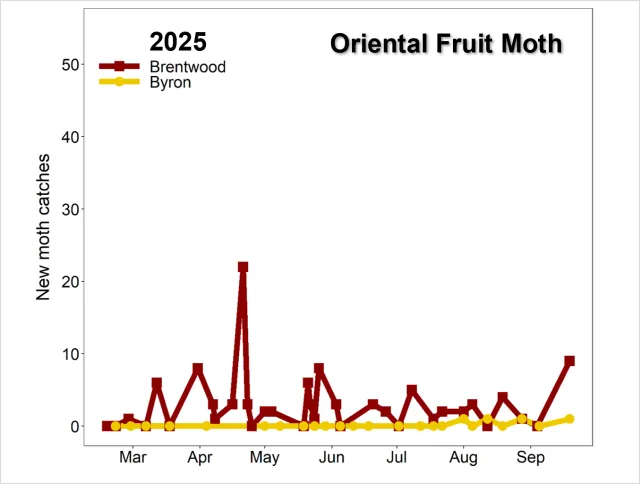

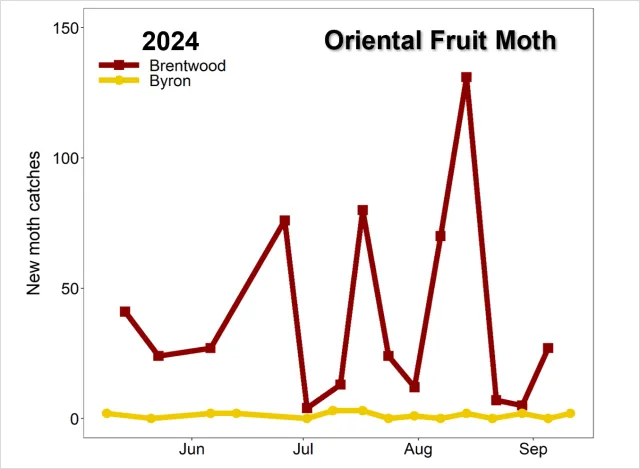

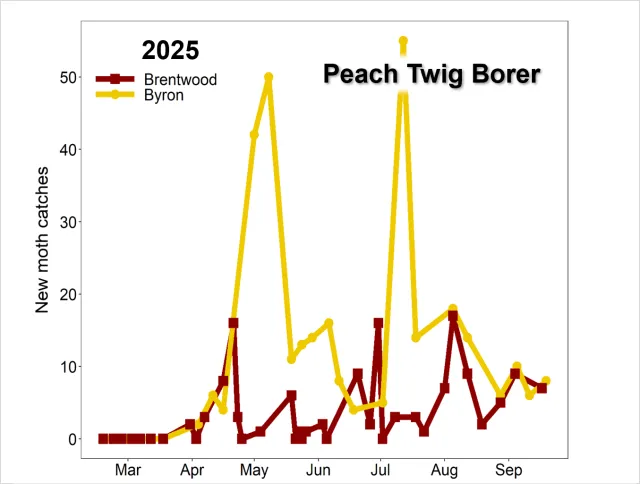

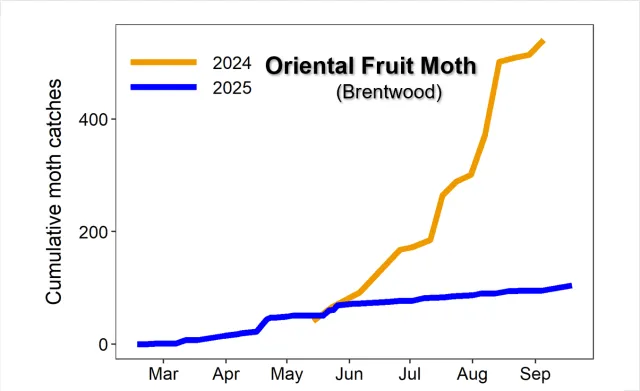

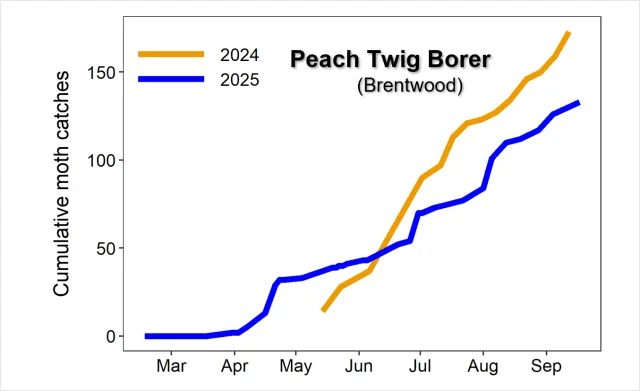

What we learned from monitoring: So with all of that said, what can we learn from the results of OFM and PTB monitoring in eastern Contra Costa county over the past two seasons? In collaboration with local fruit growers, my Mt. Diablo Region specialty crops program monitored these pests in two stone fruit orchards in Brentwood and Byron in 2024 and 2025 using pheromone baited sticky traps. In 2025 we started early enough to catch the first occurrence of adult moths. For OFM, this was on Feb. 27 in Brentwood but we did not catch a single OFM in Byron until Aug. 1st. In contrast, PTB first showed up in traps on 31 Mar. in Brentwood and on 4 Apr. in Byron. The date of first capture of adults in traps (called a "biofix") is important as this is when the degree day models are initiated (as mentioned above, a post dedicated to that topic to come soon). Comparing the number of new OFM caught in traps for 2024 and 2025 (figure 1), you can note a few important patterns. First, OFM was rarely seen in Byron, but occurred sometimes in high numbers in Brentwood. Second, in 2024, we can see at least three distinct OFM flights in Brentwood between June and September, whereas numbers in 2025 were much lower, and perhaps two distinct flights could be identified. For PTB in 2025 (figure 2), the graph shows two to three distinct flights occurring at roughly the same time in both areas, but trap catches were much higher in Byron than in Brentwood. Looking at graphs showing cumulative catches for each pest (figure 3), we can see that there was a great seasonal difference for OFM in Brentwood, while PTB numbers were somewhat similar across years. These numbers show that there can be great differences in pressure from these pests between two relatively nearby sites and also at the same site across years. This highlights the importance of monitoring for pests to make informed decisions about pest management. This is the consideration of pest biology in management decisions that is a cornerstone of integrated pest management and sustainable pest management practices.

Ready to try it? Are you convinced about pest monitoring as an essential management tool, or at least curious to learn more? If you are a stone fruit grower in the Alameda or Contra Costa county, you can reach out to me for more information and for possible opportunities to try out trap-based monitoring in your orchard.

References and Sources:

University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management (UC IPM) Agricultural Pest Management Page for Oriental Fruit Moth (Grapholita molesta)

University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management (UC IPM) Agricultural Pest Management Page for Peach Twig Borer (Anarsia lineatella)

UC IPM Natural Enemies Gallery

UC IPM Biological Control and Natural Enemies of Invertebrates