Infestations of Medusahead can be suppressed by targeted grazing

Medusahead (Elymus caput-medusae) is a common invasive grass on California’s annual rangelands. It accumulates high levels of silica as it matures, making it unpalatable to livestock and slow to decompose. As a result, livestock tend to avoid it for more desirable forage, potentially allowing it to form a dense thatch layer that persists on the landscape. This can suppress more desirable forage species and allows medusahead to spread over time.1,2

Medusahead seeds remain viable for only a few years, so disrupting seed development can control infestations. While herbicides and mechanical removal are viable control methods, we explored whether high intensity, targeted grazing guided by virtual fencing (VF) could offer an effective and practical alternative.1,2 Fortunately, there is a brief window when the developing plant has produced immature seeds and has not yet accumulated high silica levels.3 During this time cattle may find medusahead palatable enough to consume, potentially interrupting its reproductive cycle.4

UC Cooperative Extension Central Sierra Advisors used Virtual Fencing for targeted grazing

In May of 2024, we used Virtual Fencing (VF) to concentrate 25 steers and heifers on a 3-acre Medusahead infestation along a fenceline within a larger pasture in Amador County. Water and shade were provided within the enclosure. The livestock stayed in the VF area 100% of the time for nine days. On the tenth day, however, the livestock left the area, presumably for better forage. Despite this escape at the end, we were satisfied with the result.

Only 5.6% of the pasture in the target area still had ungrazed Medusahead with viable seed heads that could grow next season, whereas immediately adjacent to the grazing area, ungrazed Medusahead had turned into a thatch that covered 87.3% of the pasture (Figure 1). All animals gained weight during the trial.

Figure 1. Left: The viewer's left demonstrates the impact of high-intensity, short duration grazing on immature medusahead, contrasted with the ungrazed control area showing high levels of medusahead infestation, identifiable by its glossy yellow green color. The VF boundary is visualized by a line in the pasture that the animals are trained not to cross. Right: VF collar location data (blue dots) during the trial. The VF boundary is represented by a yellow line and the barbed wire fence is represented by a white line.

Effects of high intensity targeted grazing using VF collar

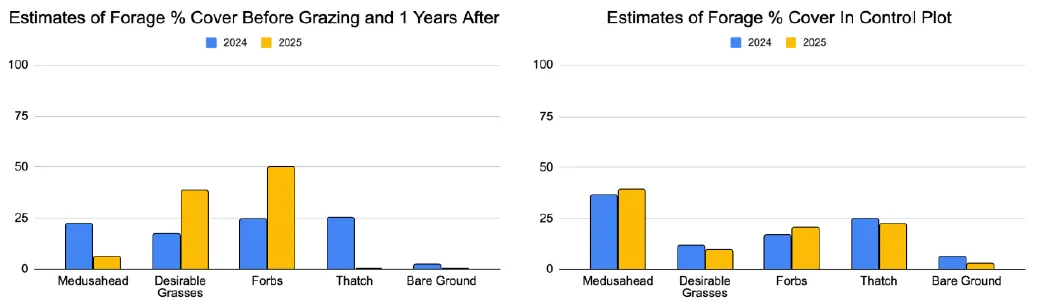

The effects of this single high intensity targeted grazing treatment carried over into the following year. While the control plot remained nearly unchanged, the grazed plot displayed the following improvements one year later compared to the original condition:

- Medusahead cover remained far lower in the grazed plot, from 22% originally to 6%.

- Other grasses and broadleaf plants (forbs) doubled.

- Thatch cover was nearly eliminated.

- Bare ground remained low.

Figure 2. Estimated percentage cover of vegetation types immediately before the grazing trial (blue) and one year after (gold). Left: Impacts of grazing on vegetation types. Right: Ungrazed control.

Results of this Virtual Fencing grazing trial

These results suggest that virtual fencing has merit as a tool for targeted grazing of medusahead during its short vulnerable phase, offering ranchers and land managers a flexible and labor-saving option to improve rangeland health. Currently, we are conducting a similar trial on barbed goatgrass (Aegilops triuncialis), a similar problematic annual grass weed. We are excited to share those results with you in the future.

Want to learn more?

Reach out to Brian Allen at brallen@ucanr.edu

References

1.George, M. R. (1992). Ecology and management of medusahead. University of California Range Science Report, 23, 1-3.

2.Young, J. A. (1992). Ecology and management of medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae ssp. asperum [Simk.] Melderis). The Great Basin Naturalist, 245-252.

3.Murphy, A. H., & Turner, D. (1959). A study of the germination of medusa-head seed.

4.DiTomaso, J. M., & Smith, B. S. (2012). Linking ecological principles to tools and strategies in an EBIPM program. Rangelands, 34(6), 30-34.